Apies River Rehabilitation Progress Report and Motivation for Subsequent Phases

Siegwalt U Küsel

Prof L Arch (SA) Reg. no. 20182 ASAPA no. 367

Principal Landscape Architect & Archaeologist

The Apies River is inextricably linked to the history of the City and its people. Historically it was the very presence of this river system and the associated productive soils that enticed people to settle along the banks. Over time as our dependence and reliance on the river waned, we have forsaken the river and reduced it to little more than a conduit for stormwater.

Although the Apies River is recognised as a critical open space resource (Tshwane Open Space Framework 2005) the system has been substantially degraded and impacted by urbanization. While it is widely recognised that an open space system potentially brings many benefits, what is less widely acknowledged is that if the responsibilities for the management and maintenance of the space are not clear, the space becomes invaded and overgrown and perceived to be unsafe. The space may then become more of a problem than an asset.

According to the River Health Programme, State of the Rivers Report (2005: 24) the ecological functioning of the river is marginal/low due to the fact that in- tream habitat integrity, riparian zone integrity, riparian vegetation integrity, fish assemblage integrity, macro-invertebrate integrity and water quality are all regarded as poor. The key drivers of change have been the high levels of urbanization and the associated changes in hydrology as well as morphological changes of the Apies River. According to this report the urgently required management responses must seek to:

- Restore and rehabilitate channel morphology and riparian vegetation;

- Control urban runoff, which is impacting on water quality;

- Reduction solid waste pollution.

Figure 1. The state of the river prior to the commencement of rehabilitation. Note the extent of dumped material in the bank profile.

Figure 2. The first section of river to be rehabilitated.

Streams and river corridors develop in response to the surrounding ecosystems and any changes within the ecosystem have a cause and effect impact on the river or river corridor. In a stable catchment, rivers develop to a state of ‘dynamic equilibrium’. This state of equilibrium is established for the catchment-specific natural range of variables that typically include aspects such as sediment, biotic process, flow regimes and climate.

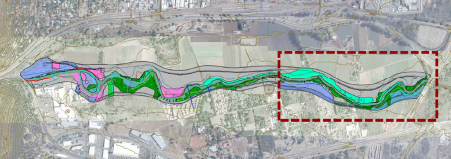

Once anthropocentric impacts or disturbance exceed the thresholds of ‘dynamic equilibrium’ the river environment moves into a state on instability until a new state of ‘dynamic equilibrium’ can be reached. Over time the development of the City has impacted severely on the Apies River corridor. Varying demands from agriculture, the industrial sector, commercial and residential development, transport and a range of other factors have placed heavy demands on the river corridor. Cumulative effects of these activities have resulted in significant changes to both the river corridor and the ecosystem. These changes include habitat destruction, loss of water storage capacity, altered flow regimes, water quality degradation, physical and structural changes to river morphology, and decreased aesthetic quality and recreation opportunities. Further to this several existing developments in proximity to the river are now threatened by flooding. In this contest the rehabilitation of this river has been in the planning stages for nearly 20 year before finally the first phase of the rehabilitation commenced as part of the bulk service contributions of the Rainbow Junction development in June 2019. The first phase is the rehabilitation of a one-kilometer section of river directly south of the Onderstepoort K8 Bridge (Rosslyn Bridge).

In the six months that we were in the construction period we have seen drastic and dramatic changes in the river and surrounding environment. The construction phase focused on the removal of illegal dumping, the restoration of bank profiles, bioengineering protection and revegetation. We are currently and the initial 6-month growing-in phase and this will be followed by a further 2 years maintenance phase to help the river get back to a state of dynamic equilibrium. From a dumping ground overgrown with reeds and weeds, the river has been transformed into a linear open space asset that harbours birdlife and wildlife, an asset that people want to be associated with and a resource that people want to engage and recreate with.

The following visuals illustrate some of this journey to restore the river:

Figure 3. Removal of the invasive Arundo reeds and dumping.

Figure 4. Screening of dumped material to reuse in construction.

Series of fixed-point monitoring photographs demonstrating the impact of the rehabilitation in the first 3 months.

Figure 8. Despite extensive flooding in December, by mid-February the revegetation measures

Figure 9. The commencement of the growing-in phase on the west bank, while rehabilitation on

In the short period of 6 months the river has been transformed. We have been able to remove more than 50 000 m3 of dumping (the volume of 20 Olympic swimming pools) and 20 ha of exotic and invasive vegetation. This has been replaced by 20 ha of indigenous grass, sedges (280 000 wetland plugs & 700 wetland sods), 1000 shrubs and 800 trees. The stormwater systems that feed into this section of river all do so via an off-stream retention pond that help to mitigate solid waste pollution.

We have given this stretch of river a new lifeline and equipped it with a rich pallet of indigenous plant species that create a seed base to recolonize the banks and assist the river to a state of dynamic equilibrium.

Restoration of a river is not an event but a journey. We have already learned lots of lessons and seen drastic improvements. The real value and change we will see only in the years to come but people around the river have noticed the change and are once more interested to engage with a once loved but forgotten river. Now that we have started, we cannot stop.

Images and copy courtesy of

Prof L Arch (SA)

Principal Landscape Architect & Archaeologist